|

|

|

|

In Lieu of a Blog

Peter A. Taylor

Last update October, 2021

This started out as an overflow file for short notes related to the

BAUUC Conservative Covenant Group (CCG). Now it's just a mish-mash of short articles that didn't seem to belong anywhere else.

Table of Contents

Epistemology for Engineers (IE Dharma Talk #1)

I am unhappy with Jerry Pournelle's treatment of rationality in "All Ends of the Spectrum". He has several groups of people with wildly conflicting political beliefs (Objectivists and Communists) that he labels as "rational" to an extreme, and other groups (hippies and conservatives) that he labels "irrational", some of which I think are quite reasonable. The question I think people need to ask themselves is, "How do I know that my political ideas are right?" (aka epistemology). There are several ways to answer this question, and they don't necessarily conform to positions on a single axis.

I am an engineer by trade. Specifically, I'm a stress analyst. I sometimes sign drawings on behalf of the stress group. I have to ask myself a similar question: "How do I know that this design is safe?"

One answer is that in some cases, I may trust my intuition. I might be asked to sign a document that might be an instruction to count the number of M&Ms that go into an astronaut's lunch box. This is a no-brainer. I may say, "engineering judgement" or "by inspection", but what this really means is that this question is so easy that I trust my intuition.

A second answer is that in some cases I trust my analysis tools. The drawing may be for an aluminum bracket with a stable cross-section and well-understood loading conditions. I can perform an analysis or review someone else's analysis and trust the results.

A third answer is that I may not trust my analysis tools, but I have test data. I might not trust computer software that attempts to predict the performance of a parachute, but I would trust a well-thought out series of tests. The questions I would ask would be whether the number of experiment runs is large enough to give reliable results and whether the experiment conditions are known to be realistic.

Any of these answers might be rational or not, depending on whether the chosen approach fits the circumstances.

In a political context, religious conservatives often have large experience bases, but instead of arguing in terms of this "test data", they claim that their rules have ancient supernatural provenance. The claims of supernatural provenance may be irrational, but making decisions based on large experience bases strikes me as eminently reasonable.

Update: David Throop followed this with a discussion of a Rod Dreher article,

Sex, Communism, and Machines, as an alternative to Pournelle's rationality axis. After all, which do you think is a more powerful force in human affairs, rationality or sex?

Also, note Bryan Caplan's distinction between

epistemic and instrumental rationality. A politician who convinces himself that 2 + 2 = 5 is irrational in the epistemic sense, but if it gets him elected, it is rational in the instrumental sense.

Is atheism a religion? Theology from a statistician's perspective

This is a slightly edited reply to a discussion on the Larry Niven science fiction email list back in 2007.

> My argument was and remains that you don't get to call yourself the

> more rational side of the argument when your side is as devoted to

> claiming an unprovable as fact as the other side. Both are irrational.

I. J. Good (statistics professor and WWII codebreaker) gave a lecture to the Virginia Tech Philosophy Club sometime back around 1980 on a subject along the lines of "What makes a reasonable person think that a theory is true?" (Beware early Alzheimer's on my part!) One consideration is that a good theory has to be consistent with our observations. The second consideration is parsimony (Occam's Razor). The third consideration is a high initial probability of being true. This is closely related to parsimony. For example, if I think there is a high initial probability of a person behaving selfishly, then an "economic" explanation of his behavior in terms of self-interest will strike me as more parsimonious than a psychological explanation involving unconscious animosity toward his mother. This initial probability factor helps make people's reasoning processes subjective, irreproducible, and sensitive to seemingly minor or irrelevant things. In the context of religion, I find the initial probability of the sort of God that Deists believe in to be much greater than the initial probability of the God of the Old Testament. It is entirely appropriate and unavoidable that people's judgment will be colored by this sort of thing.

The issue of whether the absence of belief is equivalent to belief in the absence begs to be discussed in terms of probability and confidence. In strict philosophical terms, it may not be possible to be absolutely sure of anything, but there is still such a thing as "good enough." If "faith" means acting in the face of honest uncertainty, then I don't see anything wrong or irrational with it, but I will still object to people lying about uncertainty. It is also fair to ask whether someone is using consistent standards of evidence. My estimate of the probability of the existence of the God of the Old Testament is low enough, and my confidence in that estimate is high enough, that I will treat this probability as being zero for purposes of eating pork. Is this atheism or agnosticism? Is it rational? Does it constitute a religion?

Is atheism a religion? Is black a color? For purposes of buying paint, yes. For purposes of doing spectragraphic analysis, no. What wavelength of light is the color, "black?"

When I originally wrote the above, I didn't realize that Good was a statistician, but I now recognize his "initial probability of being true" as a "Bayesian prior" as described by Eliezer Yudkowsky. Yudkowsky is obsessed with the nature of rationality, and his "Bayescraft" is an essential aspect of it.

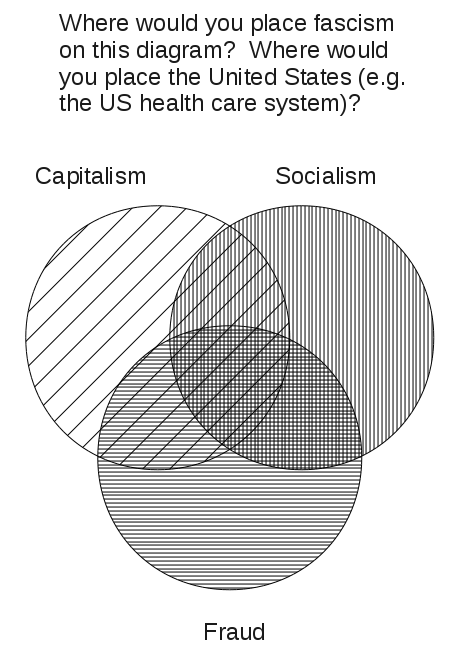

Fascism: A Venn Diagram

See Sheldon Richman's article on fascism at The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. He begins his article:

As an economic system, fascism is socialism with a capitalist veneer.

Do you think of fascism as primarily an economic system with some foreign policy and racial baggage, primarily as foreign policy with economic and racial baggage, or primarily as racism with economic and foreign policy baggage? Historically, the economic view strikes me as the most accurate, but it is the least politically convenient.

Update: see also Daniel Hannen on fascism's socialist roots:

Hitler told Hermann Rauschning, a Prussian who briefly worked for the Nazis before rejecting them and fleeing the country, that he had admired much of the thinking of the revolutionaries he had known as a young man; but he felt that they had been talkers, not doers. "I have put into practice what these peddlers and pen pushers have timidly begun," he boasted, adding that "the whole of National Socialism" was "based on Marx".

Also,

Of what importance is all that, if I range men firmly within a discipline they cannot escape? Let them own land or factories as much as they please. The decisive factor is that the State, through the Party, is supreme over them regardless of whether they are owners or workers. All that is unessential; our socialism goes far deeper. It establishes a relationship of the individual to the State, the national community. Why need we trouble to socialize banks and factories? We socialize human beings.

— Hitler Speaks, by Hermann Rauschning, London, T. Butterworth, 1940 (quoted here)

Update: Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh was once asked to explain the relationship between the Western concept of "true self" and the Buddhist concept of "non-self". His answer was that "True self is that self which is composed entirely of non-self elements."

I found this to be a confusing answer.

I am similarly confused by the ways people use the word, "fascism". Progressives often claim that they are arch anti-fascists.

Fascism is associated with foreign military adventurism, but the Progressive, and presumably anti-fascist, Teddy Roosevelt was famously into foreign military adventurism. Fascism is associated with racism, but the Progressive, and presumably anti-fascist, Woodrow Wilson was famously racist. Fascism is associated with heavy-handed political control over nominally private economic matters, but the Progressive, and presumably anti-fascist, Franklin Roosevelt was famously into heavy-handed political control over nominally private economic matters. (Oh, and there's the street violence with the tacit approval of the relevant parts of the government, now known e.g. in Charlottesville, Virginia as "Antifa". Update, 7-25-2021: Oh, and let's talk about censorship, especially censorship by large corporations that are joined at the hip to the State.)

It would appear that true fascism is that fascism which is composed entirely of anti-fascist elements.

See also the Ayn Rand Lexicon.

Update: George Orwell ends his 1944 essay, What is Fascism?, with the following paragraph:

But Fascism is also a political and economic system. Why, then, cannot we have a clear and generally accepted definition of it? Alas! we shall not get one — not yet, anyway. To say why would take too long, but basically it is because it is impossible to define Fascism satisfactorily without making admissions which neither the Fascists themselves, nor the Conservatives, nor Socialists of any colour, are willing to make. All one can do for the moment is to use the word with a certain amount of circumspection and not, as is usually done, degrade it to the level of a swearword.

Comments on Liberal Fascism, by Jonah Goldberg

I finally (2-25-2012) finished Jonah Goldberg's Liberal Fascism. I pretty much agree with Arnold Kling's review of it, but I divide the book up slightly differently. The book has three layers. One layer is an intellectual history of the left over the last century or so. That layer is quite good, IMHO. A second layer is a complaint about the misuse of language. This layer needs to have been written by ... someone like George Orwell, who cares deeply about language, has an ear for it, and is willing to be pedantic about it. Goldberg fails here. You have to be pedantic to write a book like this, and Goldberg isn't anywhere near pedantic enough. The third layer is what Kling describes as Goldberg being a troll. This layer also irritates me, because Goldberg keeps vacillating. He walks up to his target, raises his sword, and then backs away. This is closely related to my complaint about the second layer. Goldberg never really nails down a consistent definition or enumerates a set of distinct definitions of "fascism," or, for that matter, "Marxism," another key term needing a clear definition. Goldberg had me eating out of his hand for the first 22 pages, informally describing where the fascists were coming from. But then, on p. 23, he tried to give a formal definition, which was essentially that it was a synonym for totalitarianism. This wasn't really consistent with the previous 22 pages, and it is not really helpful. He lost me there on p. 23, and he never really got me back.

If I were the editor of a second edition of this book, I would demand that Goldberg put a glossary in the front of it, with numbered definitions for all of the conflicting usages of words like "fascism," "Marxism," etc. Then I would demand that every time he used one of those words, he put a subscript on it indicating which usage he was referring to.

Kling links to a Bloggingheads diavlog between Goldberg and Will Wilkinson that I thought was worth the 75 minutes. I would have liked to have heard more about the Social Gospel, though. I am still undecided about whether to think of socialism as a Christian heresy or as something fundamentally alien to Christianity.

Even if I think of socialism as an evolutionary fork of Christianity, there comes a point where one has to say that mammals may have evolved from reptiles, but the two classes are now distinct. But socialist impulses are too old for me to be happy with that analogy. A better analogy might be a recurring infection, like shingles. Another analogy might be that the Social Gospel is to Christianity as a hermit crab is to the empty shell of a nautilus.

I keep thinking of a remark by Richard Fernandez, quoting Mark Lilla:

"Religion is simply too entwined with our moral experience ever to be disentangled from it, and morality is inseparable from politics." But that underrated the ambition of the ideologues. Once God had left the room the stakes went too high: and God's vacant throne glittered irresistibly before them.

Comments on The Antiracism Trainings, by David Reich

I finished reading The Antiracism Trainings, by David Reich, a thinly fictionalized account of his time as editor of the UU World. It takes place at the "Liberal Religion Center" at 47 Beacon Street in Boston, as opposed to the UUA at 25 Beacon Street.

I think the book can be summed up fairly well by quoting a short section from p. 300 regarding the power struggle for editorial control of the church magazine:

As Ginny speaks, I come to a realization that I should have attained some years ago: that in taking on antiracism, we have taken on a discipline, a vested interest, a career path. It's not just Mal Bond and his perks we're opposing but thousands, probably tens of thousands of professional antiracism workers, in the colleges and governments, the churches and the charities. Tens of thousands of professional antiracism workers and their jealously guarded livelihoods!

Here is a pretty good review, except that the reviewer doesn't seem to know about Unitarian Universalism, and doesn't seem to realize that this "novel" is only superficially fictional. He writes, "sadness lurks underneath the humor," but for me, the book was too true to be funny.

Related to this is a bloggingheads diavlog (August 2nd, 2010) between Glenn Loury and John McWhorter on "Post-Post-Racial America." Note the section labelled, "The collapsing regime of political correctness."

An Industrial Engineering perspective on Racism (IE Dharma Talk #2)

There were three decision-making domains that were discussed in one of my Industrial Engineering classes: (1) deterministic decision-making, where you have all the information you need, (2) decision-making under risk, where you have to gamble, but you know the odds, and (3) decision-making under uncertainty, where you have to gamble and you don't even know the odds.

In Martin Luther King, Jr's famous "I have a dream" speech, he says that we should judge a man based on the content of his character rather than on the color of his skin. This makes perfect sense in the context of deterministic decision-making. If I know your character, I should judge you based on your character. But what if I don't know you well enough to judge you based on your character? What if I have to make a snap decision, and don't have the time, or it's impossible or would be prohibitively expensive for me to investigate you thoroughly enough to be confident of my knowledge of you? Consider the following scenario:

There are two populations of space aliens, who have come to Earth as refugees from a supernova, the Greens and the Grays. I want to hire one of them as an accountant for my business, but I want one who's honest. I have a statistical basis for thinking that 10% of the Grays, and 40% of the Greens, are crooks. I have also found that a test I use as part of my job interview process to detect crooks gives true negatives 70% of the time of the time I administer it to reliable long-term employees (30% false positives), and true positives 60% of the time I administer it to known crooks (40% false negatives). I have two applicants: Nigel, a Green, tested negative for crookedness. Dan, a Gray, tested positive for crookedness. I estimate, using Bayes' theorem:

P(Nigel is a crook) = 0.40*0.40 / ( 0.40*0.40 + 0.70*(1-0.40) ) = 0.27586

P(Dan is a crook) = 0.60*0.10 / ( 0.60*0.10 + 0.30*(1-0.10) ) = 0.18182

Which applicant should I hire?

Is this racist? If so, is it racist because my inputs are incorrect, or because I am using correct inputs in a situation in which I am morally obligated to lie about them? Is it racist because I am applying Bayes' theorem incorrectly, or because I am applying it correctly? Have I made an error, or is Bayes' theorem just inherently sinful?

Some people define "racism" in terms of a fallacy of division, attributing statistically average characteristics to all of the members of a population (e.g. Nicholas Wade, A Troublesome Inheritance). In other words, "racism" is failure to update one's Bayesian priors, i.e. failure to take new information into account. This seems to me like a very unsatisfactory definition for two reasons:

[Update: Vox Day points out that the Oxford Dictionary definition of "racism" is such an utter straw man that it is logically impossible for anyone who understands probability theory to be a "racist".]

I'm left with the impression that the whole point of antiracism is to force people to lie about their Bayesian priors. This is often accompanied by a second lie to cover up the first, by claiming falsely that they have enough information to make the relevant decisions deterministically, thus avoiding any awkward questions about Bayesian priors.

A college roommate used to say back in the Reagan days (1980 or so) that the definition of a "racist" is anyone who's winning an argument with a "liberal".

As one commenter put it,

I'm genuinely surprised these days when the term "racist" turns out to be a neutral, accurate description — it's like finding out that a guy everyone calls a "motherfucker" is literally having sex with his mother.

Who should bear the cost of my not knowing how similar you are to other people in your statistical pool? Is there some fundamental moral principle that leads us to say that you are not your brother's keeper, but that I am?

See also my discussion of false friendship (principles 22 and 23) and anti-racism.

Update: Bayes' theorem also suggests an interpretation of "white privilege": In this scenario, Dan has "Gray privilege". If someone has to make a decision about Dan based on imperfect information, Dan benefits from the reputation of his peer group relative to Nigel's peer group. This is not evidence that the Grays or the humans are doing anything evil to the Greens, but simply a consequence of the fact that people have to make decisions with imperfect information.

I think of this as the "evil twin" problem. Suppose that I drive a tamale truck, and sell good tamales at a reasonable price. You might want to buy some tamales from me. But I have an evil twin, who drives an identical-looking tamale truck, but who sometimes poisons people. You can't tell us apart. Are you going to buy tamales from me? Or would you rather buy them from Jose, down the street, who comes from a population that makes him less likely to have an evil twin?

Dan and Nigel may both be honest, but I can't tell either of them apart from their hypothetical evil twins. Or they may both be crooked, and I can't tell them apart from their hypothetical good twins. But honest Nigel suffers more than honest Dan from being judged based on the likelihood of having an evil twin, and crooked Dan benefits more than crooked Nigel from being judged based on the likelihood of having a good twin.

A more straight-forward interpretation of "white privilege" is that it is simply a rationalization for inconsistent, politically motivated group punishment. If the Green space aliens are clients of the dominant political coalition, and the Grays are not, The Powers That Be (TPTB) would never dream of imposing collective punishment on the Greens, e.g. for things their ancestors did. "Gray privilege" is an excuse for collective punishment of the Grays in the exact same circumstances.

Update, 4-25-2022: If (1) I am a Tutsi, (2) I am looking to hire a bodyguard, (3) you apply for the bodyguard position, and (4) you are a Hutu, am I morally obligated to trust you? Does it matter if I can produce statistics about Hutus behaving badly towards Tutsis (and vice versa)? Under what circumstances am I morally obligated to trust someone?

Some people consider racial profiling to be a form of racism. I claim that racial profiling is an artifact of decision making under risk.

Update, 1-22-2023: If a random member of population A is treated as a random member of population A, and a random member of population B is treated as a random member of population B, is that "racism"? Is that "privilege"?

There is also the matter of "iatrogenic disease", disease that is caused by bad "medicine". Charles Murray was writing about this decades ago: see Losing Ground. But Murray is focused on material causes. The blogger, "Handle", has some observations about spiritual causes:

A lot of the craziness we observe and the bizarre and pathologically maladjusted personalities and neurotic, sadistic psychological neurosis on display, is in large part the accumulated damage from a lifetime of having ones envy and resentment and feelings of loser humiliation stoked and agitated. You can't stay in that mindset for long — it's spiritual poison — or it will destroy you and turn you into a monster.

Update, 3-1-2023: Does "bias" mean that my statistics are bad, or does it mean that I am correctly treating different statistical populations as being statistically different? I think an engineering professor would say the former, but a UU minister would likely say the latter.

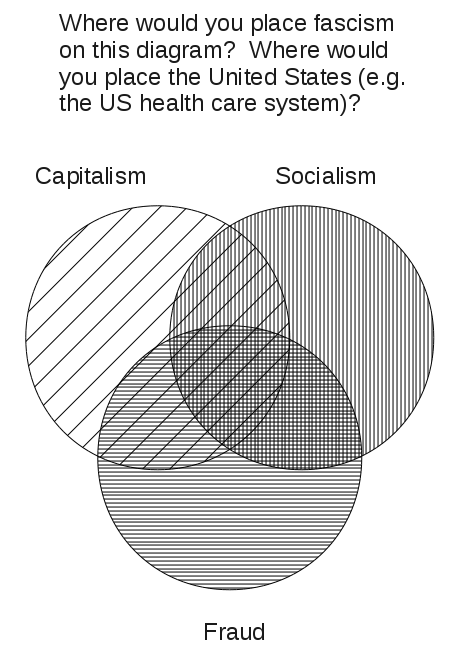

Comments on "Social Harmony and the Shrunken Choice Set", by David Friedman

David Friedman has a paper called "Many, Few, One: Social Harmony and the Shrunken Choice Set" that discusses the trade-off between freedom and equality (i.e. what libertarians want vs. what socialists want). Are the two groups condemned to work at cross purposes, or are their goals compatible? It is logically possible that their goals could be wildly incompatible, but whether they are in practice is an empirical question. Socialists might imagine a society where there was nearly perfect equality, but not necessarily much freedom. Libertarians might imagine a society where there was enormous freedom, but great inequality. But if we limit our choices to the sorts of societies that we actually know how to create, what are our actual choices? Friedman presents some figures similar to the one below. Plot all the actual historical kinds of societies you know of on a chart, comparing their attractiveness in terms of freedom vs. equality. Then draw an envelope around these points. What does this envelope look like? In case 1, there is a huge conflict between where the socialists want to be (upper left) and where the libertarians want to be (lower right). In case 2, both groups want to be at the cusp of the envelope in the upper right, and the conflict vanishes. (Friedman also shows a third case with a slightly rounded point, with a small amount of conflict.)

|

Friedman writes,

The socialist and the libertarian disagree about the relative justice of capitalist and socialist institutions. But they also disagree, often even more, on how these institutions do or will work; the capitalist society that the socialist attacks barely has a resemblance to the capitalist society that the libertarian defends. And I have yet to meet the socialist who is willing to defend the society that Hayek believes socialism would produce.

Afterthoughts:

Friedman may be correct, that rational, well-informed libertarians and socialists would support pretty nearly the same policies. But in practice, it may not be possible to prove to the satisfaction of a skeptical or biased audience that the envelope looks like case 2. If we draw our envelope based on what people can see through a fog of ignorance, propaganda, and motivated reasoning, we may end up with a gray smear that bulges out a little, but isn't different enough from case 1 to help very much. We may end up with a blurry Rorschach test.

Moral Philosophy for Engineers (IE Dharma Talk #3)

A co-worker once observed that the difference between an engineering optimization problem and an economics problem is that the engineering problem has a scalar-valued objective function and the economics problem has a vector-valued objective function. That is to say, the engineer can only serve one master, where the economist has to serve seven billion masters. In order to have a proper "optimization" problem, you have to have a single, unified figure of merit. If there are multiple valid but conflicting opinions about what's desirable, what you have is known in Industrial Engineering as "multi-objective decision-making" rather than "optimization".

Seen in this light, the gist of Arthur Leff's ethics book review, "Memorandum from the Devil" (link below), is that:

Christian philosophers (and strict monotheists in general) for the last two millenia have approached moral philosophy in a way similar to an engineering optimization problem. They believe that there is only one entity whose opinion really matters in the end. God's will is a scalar objective function, with which everyone is ultimately compelled to align himself.

Atheists, polytheists, agnostics, and deists, not believing in a single, opinionated, activist God, cannot set moral philosophy up as an engineering problem. Instead, they must approach it as an economics problem, with multiple players who have competing, valid opinions.

An engineering optimization problem is fundamentally different from an economics problem. Atheists can't just copy the Christians' approach with some minor modifications. Their conclusions about what is "good" behavior may be the same, but the way they get there is going to have to be totally different. They need to start over with a clean sheet of paper. A line of reasoning that rejects strict monotheism, yet depends on monotheism for its methodology, is incoherent at best. Many atheists seem to be "whistling past the graveyard" on this point. Any atheist who pretends that his morality is objectively optimal (based on "science") is particularly confused; "multi-objective decision making" problems do not have unique solutions, and it is not even technically correct to describe their solution as "optimization".

As an atheist, this role for God reminds me of a Lagrange multiplier. A Lagrange multiplier is one of a large number of tricks that mathematicians use in order to recast hard problems as easier problems. Mathematicians use integral transforms to convert an intractable set of differential equations into a set of algebraic equations in mathematical fairyland, where they can be solved and then transformed back. Mathematicians use Lagrange multipliers to doctor up inconvenient constrained optimization problems to make them look like unconstrained optimization problems, with much more straight-forward solutions. Monotheists use God to make an economics problem, which has a "Pareto horizon", look like an optimization problem, which has an actual solution*.

The biggest flaw in this analogy is that, once someone teaches you how to use a Lagrange multiplier, you can use it without having to believe in anything new in the physical world. In contrast, as an atheist, I can't just accept λ into my life as my own personal Lagrange multiplier, and then work moral philosophy problems as if I were a Christian. In order for the "God" approach to work, people have to actually believe in God, and society in general needs an authority who can plausibly claim to speak on God's behalf. Even among Christians, in the modern world, not enough people can agree on any such authority.

Atheists (and polytheists, agnostics, and deists) need to stop trying to ride on the Christians' coat tails and stop pretending that tastes and fashions are scientific facts. Get out a clean sheet of paper, and start working the problem as what it is, an "economics" problem.

And Christians: unless you are living in a society that has a consensus regarding who can speak on God's behalf, consider that you have the same problem the deists and atheists have. Your God mumbles too much.

Suggested reading:

Arthur Leff's Memorandum from the Devil

Arthur Leff's Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law

Another math analogy for God is complex numbers†. Imagine a world where mathematicians have learned how to solve linear differential equations using complex numbers, but have never invented trigonometry. A group of rationalists object: "The square root of negative one? What kind of nonsense is that?!" They refuse to use complex numbers, but they never developed an alternative that worked tolerably well. The rationalists' sympathizers are forced to choose between getting a good answer in a nonsensical way, or getting a bad answer in a plausible way.

*Alternately, one could say that the superiority of one point on the Pareto horizon over another is a credence good (unprovable). God is a Lagrange multiplier that transforms an implausible meta-ethics credence good problem into a more plausible theological credence good problem.

†I imagine an electrical engineer writing, not The Book of J, but The Book of j.

Why do I remain in UU if I'm a "conservative"?

The Thursday men's lunch group. My advice to visitors on the old soc.religion.unitarian-univ newsgroup, asking what to expect at a UU church, was to tell them to show up early and go to the adult discussion group, then sit through the service and ignore anything you don't like while you wait for the group to announce where they were going for lunch to continue the discussion. The men's group used to be more active, doing things besides Thursday lunches, and the group at my old church used to be much more active. I still miss it.

Constitutive beliefs, which I discuss here. The beliefs in substitutive atonement, the divinity of Jesus, etc. at any normal church are deal-breakers for me.

Our church is an important part of my wife's and son's* social lives. Finding a group of people who can put up with my family is a non-trivial problem. I sometimes compare our dojang to a church, but it's really not comparable (and the dojang couldn't put up with my son).

Even for my daughter, UU is better than what Sam Keen calls "the religion of the mall" (audio tape, "Living the Questions").

I should also mention that we had a house fire some years ago, and the people from BAUUC were instrumental in keeping us sane.

As much as I complain about UU, they put up with me.

* Update, 7-10-2018: My son has quit BAUUC and has lately been attending a Baptist church with some friends of ours from martial arts. He finds that it's easier to be an atheist at a Baptist church than a conservative at a UU church.

Update: Rev. Beisner gave a sermon (or presentation?) on 11-27-2016, on whether UUs "can believe whatever they want." I am now enlightened.

My interpretation:

We do have a creedal test, but it is vague and informal. Also, contra Rev. Davidson Loehr, the test has little to do with the Seven Banalities Principles. The test is that you have to be somewhat aligned with PC (e.g. pro-abortion), but there isn't a bright line. Instead, there are blurry "one of us" vs. "not one of us" decisions made by the various members that you meet. There also isn't a formal shunning process. Instead, each member looks at his blurry, subjective "not one of us" rating of you, and turns on a sort of throttleable emotional stink gland accordingly.

It's possible to get kicked out formally, for being rude or disruptive. But most people who get driven out are driven out because they get sprayed with more emotional stink than they are willing to put up with. The trick to not being driven out is to avoid political conversations with the more energetic skunks.

The revelation to me on Nov. 27 was that at least some of the clergy are openly supportive of this political creedal test. So there is an informal creed.

Tropes for a politically interesting science fiction novel

Primary elections should be held using either Approval Voting or Condorcet. I need to understand the difference between an open and a closed primary. How do they establish party membership with a closed primary? Can entryists be blackballed? One house should be elected using Condorcet, with an "agenda setter" (e.g. Speaker of the House) chosen at the national level, like the US president. The leaders of the executive branch should be chosen by the legislature, like the British do it. (See Frank H. Buckley's The Once and Future King.)

Demarchy. Have one chamber of the legislature that is chosen like a jury.

Positions of authority should be held in feudal style, as property (see the writings of Nick Szabo, especially "Jurisdiction as Property"), and should be inheritable. (In economic jargon, under democracy, political power is a "fugitive resource", i.e. "use it or lose it". This creates perverse incentives.) It should be possible to remove someone from office, but only for cause, and you have to compensate him. The new officeholder has to buy the office, like a NYC taxi driver's medallion. An officeholder should be well paid, but all of his assets held in a blind trust.

Tax authority should be roughly proportional to the degree of support in the legislature. The king should have the authority to raise some minimal level of revenue without the consent of Parliament (e.g. 5%). (This inability was a major contributing cause to the English Civil War. Refer to Mike Duncan's Revolutions podcasts.) A majority in Parliament can raise an additional amount, up to some threshold (10%?). A supermajority (e.g. 2/3) can raise an additional amount (up to 20%).

There should be a procedure for forcibly removing a bad king, but it should be costly, above and beyond having to buy his medallion back from him. Russian roulette?

There should be random Mancur Olson-style constitutional changes, simulating the loss of a disasterous war. Once a year, someone rolls percentile dice, and if the roll is 00, the entire existing government is fired and banned for life from any further involvement in government. One way to implement this would be to have two constitutions, one monarchist and one republican, one in power and the other waiting as a shadow government. Alternately, it could just be a different king (e.g. house of Stuart vs. house of Hanover).

Niven and Pournelle's Oath of Fealty. It's been done.

Moldbug's "Patchwork". Equivalently, Erwin "Filthy Pierre" Strauss' "Proprietary Communities". These are "exit systems" rather than "voice systems". But how do you force a sovereign ruler to allow exit? If the political units are large, how do you force other units to take in the refugees? If they are small, how do they defend themselves? Strauss' "basement nukes"? If proprietorship is through joint stock companies, it is important that shares be concentrated among relatively small numbers of large investors.

Is there a reason why spending decisions should be made by the same body as lawmaking decisions? Who would enforce a "takings" clause? How do you control off-budget legislative transfers?

It should be possible to sue a politician for breach of promise. (But if the legal system is corrupt, what's the point?)

Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) (thoughts on the USA's current trajectory)

(If it is not obvious to you that an open border policy is a problem, I strongly recommend reading my Response to Rev. Matt Tittle on Border Policy).

July, 2016: Regarding the Trump candidacy, I'm not sure what I should be hoping for. What is the most attractive feasible outcome for the US? My metaphor here is an airplane that is in danger of crashing. There are several different viewpoints that I have seen among the people I hang out with on the internet:

We could pull out of this dive and return to level flight (a Harding/Coolidge "return to normalcy", the old classically liberal US), and this is desirable. This view implies I should vote for Trump so that uncontrolled and in some cases malevolently controlled immigration, i.e. the importation of dysfunctional political cultures, can be stopped (also so that freedom of speech can be restored). Also, the GOP needs to be reformed*.

See Education Realist and me on immigration, and Free Northerner and me on freedom of speech.

A "return to normalcy" is impossible. We could "save" the US in the sense of preserving the Union and maintaining much of its economic and military power for use by the political elites, but it's not actually in the best interest of the average American and/or the rest of the world to do so. (A lot of the good that the US has done in the world has been in putting down problems such as the USSR that the US helped create or exacerbate in the first place. See also Libya, Syria, and arguably Ukraine.) The American people would be better off disolving the Union and forcing the state governments to compete with one another. Failing a dissolution, the US would be better off following the British example of restoring the monarchy after the death of Oliver Cromwell. In this view, democracy is not the cause of liberty but a disease that attacks it. I am also reminded of Eric Raymond's complaint against Steve Jobs, of having taken a bad model (the "walled garden" model of the computer industry) and having made it look attractive. A healthy society can get away with democracy and make it look good (for a while), but a less healthy society (e.g. Venezuela) that tries it will quickly suffer a catastrophe. So the US, under democracy, is sort of the Typhoid Mary of nations. The best way to bring about a Restoration is to starve the political system of its ability to pay its supporters by encouraging the federal government to go bankrupt and, assuming Clinton is nominated, to make a lot of enemies.

This doesn't necessarily mean literally restoring a monarchy, but it does mean switching to some other system that is less vulnerable to demagoguery than the current system.

This view implies that I should deliberately try to crash the airplane by voting for Sanders or Clinton.

The airplane analogy is bad. We're more like a hot air balloon, fueled by some moral capital that we have largely burned through. We won't have a violent crash, we'll just sort of sink into a swamp, a Brezhnevian sclerosis, and there doesn't appear to be anything we can do about it, except try to slow the rate of descent a little. This view implies I should vote for Trump, again because of immigration and free speech, but with little hope for the long term.

We can't avoid a crash, but we can delay it and make it softer, which is desirable so that more people will have time to get a clue and so that more of the old classical liberal US institutions will survive for us to build something else with. This implies voting for Trump.

We can't avoid a crash, but we can accelerate it and make it more sudden, which is desirable so that more people who remember the good old classical liberal US will still be alive to build something else with, and the sudden sharp pain will make the failure harder for the stupid people to deny. This implies voting for Sanders or Clinton.

Another view is that a Trump presidency (or even a close election) may not accomplish anything concrete, but a major election still matters to people because it affects the perceived social status of the Progressives, their allies, and their opponents. Robin Hanson argues that social status is what actually drives the behavior of most voters. The sweet, sweet tears of the Progressives are just too delicious to pass up, better than the necter of the gods. And in the long run, the best way to persuade the masses of the errors of Progressivism may well be to get them to associate Progressivism with low status. The best conservative political rhetoric may be raucous laughter while giving Hillary Clinton a swirlie.

See Robin Hanson and me. Also, Pax Dickinson sees a dietary change for the GOP establishment.

* EmpireOfJeff, via Ken Mitchell, explains what "reformed" means:

You "conservative" "pundits" still don't get it: Trump isn't our candidate. He's our murder weapon. And the GOP is our victim. We good, now?

Sam Keen's seven questions from "Living the Questions"

June, 2017: At a recent men's group lunch, I was talking about a Sam Keen tape called "Living the Questions." Keen said that there were seven questions that any good religion should answer. One of the men asked me what the seven questions were, so I gave the tape another listen. Here are the questions:

Where did I come from? (Where did everything come from? Why is there something rather than nothing?)

Where am I going? (Is there an afterlife?)

Who's in charge? (God? Male clergy? Patriarchy? Who should have power and authority?)

Why is there evil? (Who is guilty?)

Who are my people? (This is closely related to the previous question. The guilty ones are not my people.)

How close should I be to various people (e.g. my wife)?

What's the map for human life? (Where am I now? What time is it?)

Some other questions that came up on the tape:

What should I be asking now that the world is burning?

What do you think about when you first get up in the morning? E.g. an ecologist might ask, "Where does the water come from when I turn on the tap?"

Who was I last night? Who was I just before I woke up?

To what should I surrender?

How do you explain weird accidents (synchronicity)?

Commentary from me:

The question I have the most trouble with is #5. My answer to #7 is that life is a relay race, and it only makes sense if (1) I have a baton that's worth delivering, and (2) I have teammates who are worth delivering the baton to, which brings me back to #5. #4 is also important. Aristotle said something to the effect that any virtue carried to excess becomes a vice. What's wrong with Western civilization seems to be a characteristically Christian virtue ("universalism", in the sense of non-kin altruism) carried to excess. This is closely related to #3, because this universalism causes us to give power to irresponsible people.

Incidentally, Keen gets his title from a passage in Ranier Maria Rilke's book, Letters to a Young Poet:

You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.

Why do I want to call it "religion?"

December, 2017: At the most recent Conservative Covenant Group meeting, I was talking to Tom Piotrowski about how I thought Western Civilization needed a new religion, and Tom objected to my use of the word, "religion", to describe what I was looking for. I've had similar conversations before with other people. I've been told that once I become an atheist, I can't go back to "plain old religion", and that calling what I want "religion" brings up cultural baggage that just confuses things. I could call it a "memeplex" instead.

With apologies to Blaise Pascal, I believe that there is a Christianity-shaped hole at the center of Western civilization. Western Civilization is like a software package on a Linux computer. Western Civilization depends on a moral database that is (or was) maintained by another software package called "Christian moral philosophy". Christian moral philosophy depends on a theological software package called "Monotheism". What happened during the Enlightenment was that we did a forced uninstall of Monotheism, and now our operating system has a bunch of broken dependencies. The moral database is full of errors and malware, much of it driven by political opportunism. Atheists tend to take a cavalier attitude towards moral philosophy, not appreciating the degree to which they are riding on the Christians' coattails. Arthur Leff has written eloquently about this problem (see "The Memorandum from the Devil" and Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law). In terms of making sense on a literal level, I think that Christian theology is irreparably broken, and that we need a new support system for moral philosophy, along with the social institutions that go with it.

But the question I'm trying to answer here is, "Why do I want to call it 'religion'?"

The attraction of the word, "religion", is that it is shorter and requires less explanation than any of the alternatives I've come across. What I want to call it is "Things That Are Functionally Equivalent To Religion In Various Senses, To Varying Degrees" (TTAFETRIVSTVD), but Obi-Wan Kenobi tells me that this is not the acronym I'm looking for.

I see two problems with "religion". One problem is that it implies supernatural beliefs that a lot of the people we're talking about reject. So, for example, Mencius Moldbug's accusation of Richard Dawkins being a "crypto-Calvinist" sounds false on its face (see How Dawkins got pwned). The other problem is that the word is ambiguous. What is "plain old religion"? A "religion" is something that is religion-like in one of a myriad of different senses, and I don't know which sense is the relevant one.

On the other hand, I think that evoking "cultural baggage" is a feature, not a bug. Sociology, culture, philosophy, neuropsychology—in a word, TTAFETRIVSTVD—all of these things are complicated, interrelated, and confusing, not because the language is misleading, but because they are inherently complicated, interrelated, and confusing. Objectivists talk about "philosophy", but that's leaving out important social relationships. Kurt Vonnegut coined the word, "granfalloon" (see Cat's Cradle), but that leaves the wisdom out of the wisdom traditions. I'm told that the Latin root words of "religion" mean "tying together". That seems right to me.

Another aspect of cultural baggage is that the dominant memeplex in the USA today pretends to have transcended cultural baggage and "religion", and to therefore be simultaneously on an elevated scientific and moral platform. Calling it "religion" brings it down to a level playing field and ironically lets people think about it more objectively, as one of many competing sets of dubious claims rather than as the One True Church Institution of Scientific Fact and Moral Righteousness*.

Human societies are inherently going to be full of "credence goods", "group-fostered beliefs", non-scientific "doctrines" and "norms". This is naturally the stuff of "religion", and I don't think we have the option of not talking about it.

"Memeplex" gets close. It seems a little too dispassionate. Maybe I could get behind it if there were more auxiliary words with it. I know how to say that I'm shopping for a new "church". I don't know a good way to say that I'm shopping for a new memeplex-oriented social institution, or specifically a dominant memeplex-resistant social institution. Should I say, "coffeehouse", or specifically "reactionary coffeehouse"? That only evokes a fraction of what I'm looking for.

*With apologies to Monty Python's cat license sketch, I think of Progressivism as the Protestant "social gospel" movement with the word "God" crossed out and "Science" written in in crayon.

The unbearable whiteness of Sarah Jeong

August, 2018: Here is some required reading and some commentary:

Reihan Salam, The Utility of White-Bashing

(David French may be helpful for context.)

My commentary on Reihan Salam:

We have this David and Goliath mythology that the Christians picked up from the Jews and the Leftists picked up from the Christians. The story is that the guy who's punching up is the good guy, and the guy who's punching down is the bad guy. What this means in practice is that, if you're on top, and you're punching down, you have to lie about it. Thus we have wealthy, powerful, successful people, most of whom are white, condemning poorer, weaker, less successful people for "white privilege".

The Sarah Jeong controversy reminds me of a Monty Python sketch about a mattress salesman named Mr. Lambert, who reacts badly when someone says, "mattress", to him. The other employees at the department store have to warn the customers to say "dog kennel" instead of "mattress". Progressives have to say "race" instead of "class", because saying "class" would make it too obvious that they were punching down.

But I don't think "class" is entirely right, either. There's a religious, or implicitly religious, angle to it as well. You're allowed (for now) to have more-or-less Christian theology and still be a Progressive, but you have to accept Progressive leaders as de facto moral authorities, or else you'll be declared liturgically "white". Maybe Sarah Jeong would make more sense if we distinguish between "genetically white" and "liturgically white". It's not clear to what extent one can buy one's way out of liturgical whiteness with money, but I don't think it's any very great extent.

More strongly suggested reading:

Caitlin Flanagan on Jordan Peterson and broadening resistance to identity politics

Robert Mariani on liberalism and leftism as a "motte and bailey" argument

See also Uri Harris.

Consider, as an analogy, a religious person writing an article on the sinfulness of humanity. It's entirely possible for that article to be both a form of self-critique via acknowledgement of one's own sins and an outgroup demonisation of nonbelievers, who are much greater sinners and don't even acknowledge that they're sinners.

Likewise, it's possible for anti-white rhetoric to simultaneously be self-critical/-flagellatory and outgroup-demonising. After all, the whites engaging in this are acknowledging their own perceived flaws, but they're also distinguishing themselves from other whites by doing so.

Review of Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, by Tom Holland

October, 2020.

Thesis: Western civilization was largely forged by, and is permeated by, Christian assumptions, which are shared even by people who protest their opposition to Christianity. Feminists don costumes from The Handmaid's Tale to protest Puritanism, but they are protesting in a characteristically Puritan manner. We argue over whether abortion should be treated the same way as infanticide, but why is infanticide wrong? Why is misogyny wrong? Why is slavery wrong? Why is indifference towards the poor wrong? The criteria Westerners use to criticize Christianity are fundamentally Christian criteria.

Why do the Commies tend to get a pass for their mass murders, but the NAZIs don't? Because the Commies rationalize their behavior in a characteristically Christian way, as motivated by caring for the poor and downtrodden. The NAZIs rationalized their behavior in racial terms, and explicitly rejected Christian moral teachings.

Humanist teachings, e.g. universal human rights, purport to be universal, but historically, they were a Christian idiosyncrasy, and were anything but universal.

One thing I noticed is that Holland has a very different take on sacrifices than Jordan Peterson does. It would be interesting to get them together to talk about this. Holland reminds me of Christopher Moore's novel, Lamb, where the point of the crucifixion was to be done with sacrifices once and for all. Are sacrifices about negotiating with the future (Peterson), or are they about improving my lot at someone else's or something else's expense? It has been argued (Rene Girard?) that the psychological importance of the crucifixion is that it forces Christians to look at the scapegoating process through the eyes of the scapegoat.

One weakness of the book, in my opinion, is that it reads like a series of anecdotes. It would have been a very different book if it had been written by a social scientist like Guenter Lewy. Can it be shown statistically that Holland's thesis is true, that Western civilization is qualitatively different from other civilizations? Or does Christianity merely provide a different language for discussing issues that other religions also wrestle with, such as suttee? Lots of Hindus were also opposed to suttee. I'm convinced that it is more than just a different language, but I was pretty easy to convince, and I don't know how to persuade a skeptical audience. The truth or falsity of Holland's thesis seems too subjective.

A more serious weakness of the book is that Holland doesn't clearly articulate the limits of Christianity. Is his thesis logically falsifiable at all? Reading Dominion, I often found myself thinking of Theodore Parker's sermon, "The Transient and the Permanent in Christianity". What is the essence of Christianity? Does it have an essence? John Vervaeke emphasizes agape, but Holland does not, at least, not explicitly. Holland emphasizes, "The first shall be last and the last first." The crucified prisoner ultimately defeats the authority. The idea of "religion" itself, as something that can be separated from the "secular", is also, Holland claims, originally a Christian idea.

But what line do I have to cross in order to place myself outside of the Christian tradition? The NAZIs clearly crossed the line, but what about witchcraft accusations? Are witchcraft accusations a sign of the influence of Christianity, or a sign of its loss of influence? Robert Priest claims that there are two kinds of culture: In one kind, if something bad happens to me, my reaction is, "God must be angry with me. I'd better figure out what I'm doing wrong, and stop doing it." In the other kind, if something bad happens to me, my reaction is, "One of my neighbors must be practicing witchcraft. I'd better figure out who it is and kill him." From that perspective, making witchcraft accusations seems un-Christian. Rodney Stark claims that, until the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church generally took a dim view of witchcraft accusations, as being theologically incorrect. Local secular authorities would sometimes prosecute "witches", and the Church would sometimes prosecute the local secular authorities for doing so. Only after the 30 Years War did the Protestants and Catholics start competing with one another to prosecute witches, as a sort of advertising gimmick, after they had given up on defeating one another through force of arms. I am inclined to think that belief in witchcraft on the part of Christians is an aberration, a foreign theological invader. But I don't recall Holland discussing this question.

Aristotle wrote that any virtue carried to excess becomes a vice. To what extent are modern vices Christian virtues carried to excess? The Anglican term for this is "supererogation" (see Article 14). Do all religions have problems with supererogation (i.e. holiness arms races)? Is there a characteristically Christian way of dealing with supererogation? Catholics have a pope that can tell them to stop, at least in theory. Anglicans have Article 14, again, at least in theory. Congregationalists (i.e. Puritans), on the other hand, seem to have open entry into the role of "public sanctimony entrepreneur" (Handle's term).

I want to do some triage here. I want to divide problems into

What do I make of Christians' (and post-Christians') tendency to have "reformations", "awakenings", and other moral panics? Do I say that Christianity is a drama queen, and these moral panics are part of the characteristically Christian drama? Or do I say that these panics represent a breakdown of leadership or discipline? Does Buddhism, outside of Christian influences, have similar breakdowns? Or, in the case of witchcraft accusations, do I say that this is a result of the abandonment of Christian theology?

Does a dead billy goat stink because it's a billy goat, or because it's dead?

NAZIs rejected both Christian theology and Christian morality, but Communists were an edge case, rejecting the theology but appealing (selectively) to the moral tradition. The NAZI billy goat is dead. I'm inclined to say that the Communist billy goat is also dead, but I suspect Holland would disagree.

I think Holland would probably say that moral panics (reformations and awakenings) are characteristically Christian; that leadership may often be contested in many religions, but when this happens among Christians, it results in moral panics. I'd like to see more research in comparative religion before I embrace that position.

There are actually quite a lot of edge cases, or "heresies". Progressivism in the US seems to have developed from the Protestant "social gospel" tradition, but the modern "social justice faith" (James Lindsay's term) departs from Christianity in important ways. There is sin, but there is no real redemption. The mob that attacked Bret Weinstein at Evergreen College was interested in burning a witch, but had no interest in saving his soul or persuading him of anything (i.e. proselytizing). People like Curtis Yarvin like to use clading diagrams (genetic analogies) in talking about this, but that's not how belief systems reproduce. There is too much "horizontal gene transfer" for a clading diagram to make much sense. There are too many chimeras, beasts that are stitched together from parts with wildly different origins.

At what point can I say that someone has crossed the line, and his bad behavior is no longer an embarrassment to Christianity, but is now an embarrassment to some other system?

Also, what do I make of Christian pacifism? I don't recall Holland talking about pacifism, but it's definitely a thing, and it's easy to argue based on the gospels that it's the non-pacifist Christians who are the heretics. Anthropologist Edward Dutton has a lecture in which he compares ancient Judaism, ancient Roman culture, and Christianity. Ancient Judaism had both "positive" and "negative" ethnocentrism. The Jews were good to their in-group (their ethnic group), and hostile to outsiders. They were out-performed by the ancient Romans, who had similar positive ethnocentrism, but reduced negative ethnocentrism. The Romans were more open to cooperation with outsiders. Christianity improved on this by defining the in-group in terms of religion rather than ethnicity, making them fully open to cooperation with anyone of the same religion. But they were still able to wage holy war on the out-group. Dutton doesn't take pacifism seriously, either, and neither do I, but is a tendency towards pacifism an inherent flaw within Christianity that has to be resisted to make society work, or is it an aberration?

If Christianity is fading away, as it seems to be doing in the Western world, then what? Where do we go from here? I don't recall where he said this, but in one of his interviews, Holland asks something like, "If you cut the root off of a flower, can you still get the bloom?" I'm left with an image of Victor Frankenstein as a botanist, trying to put together and reanimate a zombie flower.

Relevant links:

The first reviewer on Amazon writes,

Tom Holland's Dominion is not a book written by a Christian apologist....

But.... in some ways, it is his lack of Christian piety and apologetic leanings that makes this book so convincing.

Jesus vs. Robert Bloch

October, 2021.

T. S. Eliot writes,

Humankind cannot bear very much reality.

Robert Bloch wrote a story called The Cheaters (Weird Tales, November 1947), about a pair of magic eyeglasses that enabled the wearer to see the truth. The story takes the form of a series of first-person vignettes about people who died after putting on the glasses. One was executed for murder after discovering that his wife was cheating on him. Another dies accidentally after discovering and foiling a plot to murder her. A third was killed in a fight after discovering someone cheating in a poker game. These stories are revealed in the fourth and final vignette to be reconstructions by the fourth protagonist. The final vignette is a suicide note by a man who put the glasses on and looks at himself in a mirror. He decided to shoot himself while wearing the glasses, so that they would be destroyed in the process.

I'm struck by the contrast between the teachings of Jesus and the teachings of Robert Bloch's fictional protagonist, Sebastian Grimm. Jesus said that the truth shall set you free. Bloch's protagonist says that the truth will shatter your self-image and make you want to put a gun to your head.

Which view of human nature do you think is more accurate?

They may not have been writing for the same audience. There was a "Rev. Ivan Stang" joke (Church of the Subgenius) in which he reports that someone once asked J. R. "Bob" Dobbs, "How come you don't practice what you preach?" Dobbs' reported reply was, "I'm not the kind of person that I'm preaching to."

If you were Sebastian Grimm, would you put the glasses on?

|

|

|

|